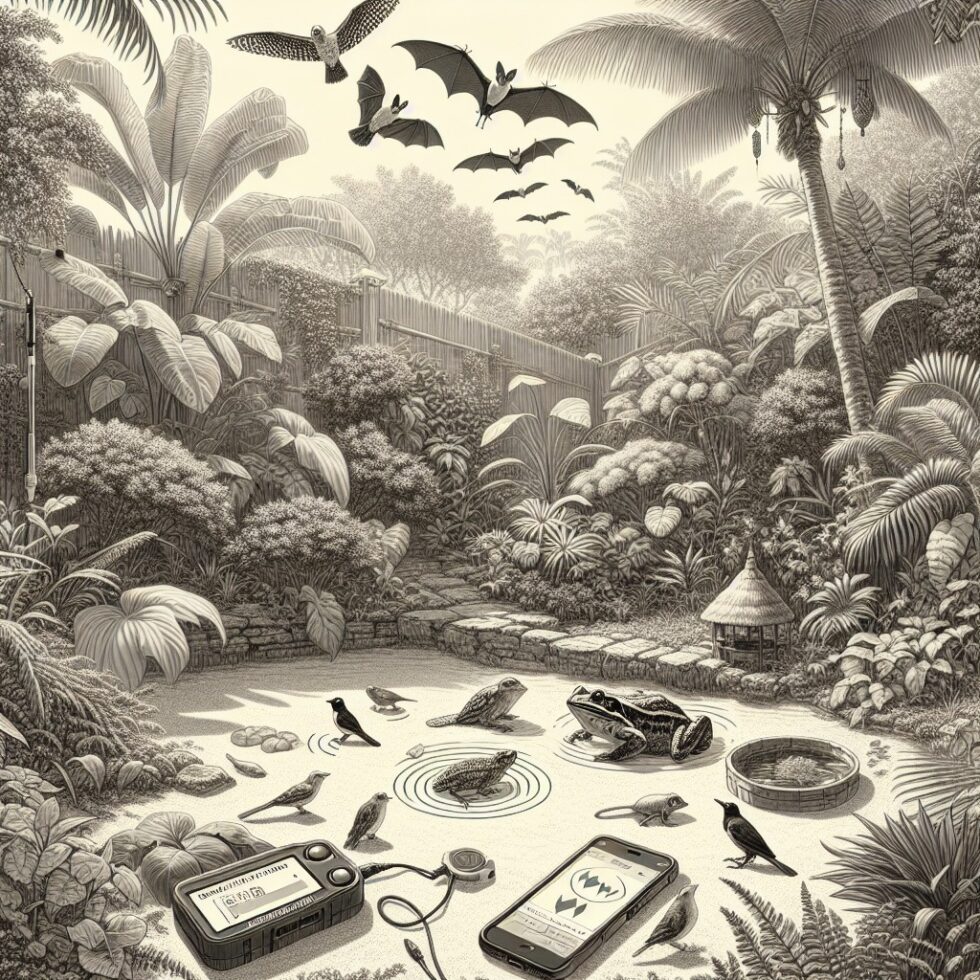

Why listen to your backyard

The fastest way to find wildlife is to hear it. Birds call from the canopy, frogs chorus at dusk, and bats whisper above 20 kHz where we can’t listen unaided. Until recently, building a rig to record, detect, and label those sounds was expensive and complicated. Today, you can do it with a phone, a $20 microphone, or a small embedded board running TinyML. This guide shows you practical ways to start, improve, and maintain a backyard bioacoustics project that actually works.

We’ll focus on getting good recordings, picking the right hardware, running reliable detection, and turning raw audio into useful information. You don’t need a lab or a grant. You need a plan, a few parts, and patience.

What you can build this weekend

Quick start: phone plus an external mic

If you want immediate results, attach a small USB-C or Lightning condenser mic to your phone, place it under an eave, and record at sunrise for 30–60 minutes. Use an app that saves WAV files at 48 kHz, 16-bit. Run the clips through a sound ID tool on your laptop to get a first species list. This teaches you about background noise, wind, and where to place the mic.

Upgrade: a tiny recorder that stays out

For reliable daily logging, use a Raspberry Pi (or similar single-board computer) with a USB microphone inside a weatherproof box. Add a small foam windscreen and a bit of mesh over the mic port. Schedule recordings at dawn and dusk with cron so you don’t fill the SD card. This setup handles birds and frogs. If you want bats, you’ll need an ultrasonic mic and higher sample rates.

Advanced: a battery-powered acoustic node

If you prefer fewer moving parts, consider a dedicated low-power recorder like an AudioMoth. It runs off AA batteries, records to a microSD card, and survives outdoors with a simple enclosure. Or go full EdgeAudioAI and compile a TensorFlow Lite Micro model onto an ESP32 or ARM Cortex-M4 board for on-device detection and alerts.

Pick the right microphone and sample rate

What are you trying to hear?

- Birds: Most bird vocalizations sit between 1–10 kHz. A 44.1 or 48 kHz sample rate is fine.

- Frogs: Depending on species, 0.3–6 kHz is typical. 44.1/48 kHz works.

- Bats: Many emit calls from 20–120 kHz. You need an ultrasonic mic and a 192 kHz (or higher) sample rate, or a bat detector that mixes down the frequency.

Pick omnidirectional mics for general listening and cardioid mics if you want to focus on a pond or tree. In windy locations, a foam windscreen is not optional—add a fur-style deadcat if you have persistent gusts.

Weatherproofing that doesn’t ruin the sound

Sound hates barriers. Water loves electronics. Your job is to keep rain away while avoiding muffling. A small roofed box with side vents protected by mesh works well. Put the mic port near the bottom with a downward-facing opening so droplets don’t enter. Don’t press mesh flush against the mic; leave a few millimeters of air gap.

Gain and clipping

Set input gain so the loudest local call peaks under 0 dBFS. Clipping makes post-processing harder and can confuse detectors. Test by playing back a phone audio clip at typical volume near the mic and checking levels. Adjust once and leave it alone.

Station placement and power

Where to mount

- Height: 2–3 meters up avoids ground echoes and reduces human noise.

- Distance from walls: Keep at least 0.5 m away from hard surfaces to reduce reflections.

- Noise sources: Avoid air vents, AC units, and rattle-prone gutters.

- Line of sight: Aim toward habitat of interest—a tree canopy, a wetland, or open sky for bats.

Power and storage

If you have mains power, a small SBC and USB mic are easy. Use a surge-protected outlet and a short, quality USB cable. For battery setups, pick a recorder designed for low-power duty cycles and budget storage at about 100–200 MB per hour for 48 kHz 16-bit mono WAV. SD cards above 64 GB are fine, but format them with exFAT and monitor for wear in long deployments.

Schedule recordings, don’t record everything

Record when wildlife is active to save power and time later. Dawn chorus is golden; dusk captures frogs and early bat activity. For bats, short bursts (5–10 seconds every minute) can still give a good sample while conserving storage. On a Pi, use cron entries to run aarecord or sox at specific times. On dedicated recorders, use built-in schedules.

From raw sound to clean data

File naming and metadata

Use filenames that pack the essentials: YYYYMMDD_HHMMSS_siteID_deviceID.wav. Keep a simple JSON or CSV “manifest” that records site location (lat/long), mic model, gain, sample rate, and enclosure details. This metadata solves 90% of debugging later.

WAV beats MP3 for detection

Compression can smear spectral details that models use. If you must compress, use FLAC to save space without losing information. For cloud uploads, batch-compress after initial detection runs.

Annotation without going insane

Start with a small labeled dataset. Open 10–20 minutes from a good morning in Audacity or Raven Lite. Add labels for clear calls—skip faint or overlapping ones at first. Save label files that include start time, end time, and species. For more examples, use reference clips from reputable repositories to learn call shapes. A little hand-labeling goes a long way for calibrating any model you use.

Detection options that actually work

Off-the-shelf: use BirdNET locally

BirdNET is a research-grade model trained on massive datasets. You can run it on a PC or single-board computer to get species predictions from WAV files. It’s accurate for many regions and can score short audio windows (e.g., 3 seconds) to localize calls. This is the fastest path to a clean species list from your recordings without custom training.

On-device TinyML for targeted detection

If you want real-time alerts for a handful of species, build a small classifier. The typical pipeline is simple:

- Slice audio into 1–2 second windows.

- Compute a mel spectrogram (e.g., 64 mel bins).

- Normalize and feed into a small CNN or CRNN (convolutional or convolutional-recurrent network).

- Set a per-class threshold and a short smoothing window to reduce false positives.

Tools like Edge Impulse can generate firmware that runs your model on a microcontroller. You’ll sacrifice broad coverage compared to BirdNET but gain speed and privacy. This approach shines for specific goals—say, detecting a rare frog at your pond or a nuisance crow near fruit trees.

Hybrid: big model for labeling, small model for alerts

Combine both. Use BirdNET on a laptop to label a week of audio. Extract clean examples of your target species and train a tiny on-device model that listens continuously and pings your phone via Wi‑Fi when confidence stays high for a few seconds. You get reliable alerts without sending continuous audio anywhere.

Quality control: thresholds, noise, and false alarms

Thresholds are your steering wheel

Lower thresholds catch more positives but increase false alarms. High thresholds miss weak calls. Start with a default (e.g., 0.6 probability) and review a random sample of detections each week. Track precision (what fraction of detections are correct) and recall (what fraction of real events were captured). Adjust per species if possible; some are more distinct than others.

Handle wind, insects, and rain

- Wind: A physical windscreen beats any filter. Add a high-pass filter around 300 Hz to reduce rumble.

- Insects: Dense choruses at night can mask frogs. Use shorter windows and higher mel resolution to separate harmonics. Consider a notch filter if a single tone dominates.

- Rain: Heavy rain degrades detection. You can auto-skip segments with high broadband energy and zero-crossing rates typical of rain.

Calibrate with spot checks

Pick 10 random detections each week and listen. Keep a log of errors by species and conditions. If the same mistakes recur, add those confusing examples to your training set or increase the decision window for that species.

Ethics, privacy, and safety

Microphones can pick up voices. Respect privacy, and make that explicit:

- Place recorders facing away from sidewalks or neighbor yards.

- Discard segments flagged by a simple voice activity detector.

- Post a small note near your yard stating that the device records wildlife sounds and is not a security microphone.

- Don’t share raw audio that includes human speech. Share species lists and short call clips without speech.

Also keep equipment secure. Mount out of sight. Use tamper-resistant screws. Label devices with a contact name in case someone finds them.

Seasonal planning: when the soundscape changes

Birds

Migration quickly changes who’s singing. Expect a surge of detections in spring mornings and quieter midday periods in summer heat. If your aim is to track arrivals, increase recording frequency during peak migration weeks and reduce it afterward.

Frogs

Frogs respond to temperature, rain, and humidity. Use weather forecasts to schedule extra evening sessions after warm rains. Maintain a notebook of first calls each year; it’s a satisfying phenology record.

Bats

Bat activity often spikes in warm, calm evenings. For ultrasonic recorders, battery life can drop faster at high sample rates. Plan shorter bursts overnight and prioritize the first few hours after dusk.

Turn data into dashboards and maps

Lightweight workflow

Keep it simple. A folder structure like /siteID/YYYY/MM/DD works wonders. Save daily species summaries as CSV with columns like timestamp, species, confidence, and duration. Use a small script to turn daily CSVs into weekly counts and a running species list.

Visualization that helps you think

- Bar charts: Top 10 species by detections per week.

- Heatmaps: Time-of-day vs. species detections to spot patterns.

- Spark lines: Per species detections over the last 30 days.

These views reveal microphone issues (a sudden drop), habitat changes (construction noise), and seasonal shifts. They also keep you motivated.

Contributing to citizen science

Best practices for sharing

Platforms like iNaturalist encourage photo or sound evidence. Upload short, clear clips of calls with accurate time and location. Try to include only the target species in the clip. For bird-specific datasets, some regional programs accept sound records; check guidelines before uploading automated detections.

Reference databases are your friend

Use large, well-curated libraries to verify your IDs and improve your model’s training data. Comparing your spectrograms with those references helps resolve tough cases, like similar trills or overlapping frequencies.

Troubleshooting field issues

Common problems and fixes

- Hum or buzz: Check ground loops, use a ferrite bead on USB cables, and keep power supplies away from antennas.

- Clipping on loud calls: Lower gain. Consider a mic with higher max SPL.

- Condensation: Add silica gel packets inside enclosures and mount under an eave. A slight downward tilt helps drainage.

- Card failures: Buy quality SD cards, format them in-device, and rotate spares every few months.

- False positives at dawn: Dawn wind and traffic increase noise. Raise thresholds during those hours or apply a gentle high-pass filter.

Ultrasonic detours: how to handle bats

Two viable routes

- Full-spectrum recording: Use an ultrasonic mic that supports 192–384 kHz sampling and record raw WAV. Analyze with a bat classifier or manually inspect spectrograms.

- Heterodyne or frequency division: Use a bat detector that mixes ultrasonics down to audible frequencies in real time. You can feed this to a standard mic and run a trained model on the shifted audio.

Full-spectrum is best for archival quality and more accurate species classification but uses more storage. Heterodyne is easy and cheap for activity monitoring and alerts.

Building a tiny classifier, end to end

Data collection

Pick one or two target species. Gather 30–60 minutes of positive examples (clear calls) across different conditions and 2–3 hours of negative/background audio. Split into train/validation/test sets. Label with start and end times for each call.

Feature extraction

Convert each 1–2 second window into a 64×64 mel spectrogram, log-scale the amplitudes, and normalize across the dataset. Save spectrograms as small float arrays or 8-bit images depending on your toolchain.

Model architecture

A 3–4 layer CNN (e.g., 3×3 convolutions with 16–32 filters, batch norm, ReLU, and max-pooling) often works. Keep parameters under 100k for microcontrollers. Use cross-entropy loss and early stopping based on validation accuracy. For multiple species, use a sigmoid output layer and treat it as multi-label.

Evaluation

Don’t chase accuracy alone. Plot precision-recall curves and pick a threshold that matches your goals. If you want to avoid false alerts, bias toward precision. If you want to catch every rare call, bias toward recall and add a manual review step.

Deployment

Export to TensorFlow Lite (or TFLite Micro) and integrate with a ring buffer that keeps the last few seconds of audio. Smooth predictions over 2–3 consecutive windows before triggering an alert. Log detections to a CSV and optionally send a push notification via Wi‑Fi when a detection is confirmed for N seconds.

Keeping it maintainable

Small habits, big gains

- Weekly 10-minute check: Listen to a few detections, confirm hardware is logging, and review storage.

- Seasonal tune-up: Adjust schedules and thresholds as migration or weather shifts.

- Version your models: Save model hashes and training notes in a README so you can trace changes in detections.

When to retrain

Retrain when you notice consistent misclassifications, add a new target species, or change microphones. Keep your old models for comparison. Evaluate with a fixed test set so you can measure improvement honestly.

Why this works now

Three trends make backyard bioacoustics more accessible than ever:

- Cheap, good mics: USB clip-on condensers and ultrasonic capsules cost less and perform better.

- Open tools: Platforms for on-device ML and research-grade models are available to hobbyists.

- Citizen science: Communities and databases make it easy to compare, learn, and share responsibly.

The result is a system you can build and grow—start with simple logs and graduate to real-time detection that fits your goals and your yard.

Summary:

- Start small: a phone and a decent mic can reveal morning birds within a day.

- Choose hardware based on targets: standard mics for birds and frogs; ultrasonic for bats.

- Weatherproof smartly: protect from rain and wind without blocking sound.

- Record on a schedule: dawn and dusk maximize useful data and save storage.

- Prefer WAV or FLAC for detection; keep filenames and metadata consistent.

- Use BirdNET for broad species ID; train TinyML models for fast, private alerts.

- Tune thresholds, review detections weekly, and manage false positives with smoothing and filters.

- Respect privacy: avoid capturing speech, post a notice, and share species data, not raw audio with voices.

- Plan for seasons: adjust schedules for migration, rain, and evening activity.

- Document your setup and model versions so you can improve with confidence.